Filed: Aug 12, 1977 – Defendants: Father Camille Léger, The RCMP & The Parishioners of Sainte-Thérèse-d’Avila Parish

Opening Statement

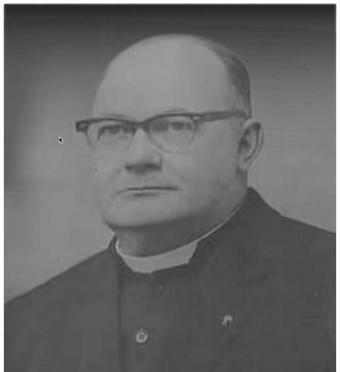

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this case takes us to a small coastal village – Cap Pelé, New Brunswick. What appeared to be a quiet community concealed a disturbing secret: for decades, the people lived under the shadow of one man – Father Camille Léger of Sainte-Thérèse-d’Avila Parish. He was not merely a priest. He was a figure of absolute authority, feared, revered, and protected.

Exhibit A: Violence at Home

Before the church entered the picture, my home life was already ruled by cruelty. My father despised me and made no secret of it. At eight, he shattered a pool cue over my head. At ten, he slammed my head in a refrigerator door for daring to seek food. On one occasion, he strangled me into unconsciousness for showing fear in his presence. Home was not a refuge. It was torment.

Exhibit B: Entrapment by the Church

My mother, desperate for help, turned to the church. That decision became her greatest regret. Father Léger persuaded her to place me in the altar boys and the Boy Scouts, both under his control. For over two years, he used those positions to abuse me sexually, physically, and psychologically.

What makes this more damning is that others knew. Members of the congregation, former parishioners, even the RCMP – they were aware of his reputation before my family ever arrived. Parents had already been pulling their children from Scouts years earlier. Yet no one warned my parents.

Exhibit C: Public Knowledge of Crimes

If the name Camille Léger sounds familiar, it’s because his actions became national news decades later. Headlines branded him a monster. Investigations estimate he abused over 250 boys – some accounts suggest far more. His crimes spanned from 1957 to 1980. He was not stopped; he was transferred. And in Cap Pelé, he continued unchecked.

Exhibit D: The Town’s Complicity

At 11, I was small for my age, nicknamed Ti-pint or Ti-boy. Every Sunday, the townspeople watched me sit beside Father Léger at the altar. They saw me. They knew the danger. And still, silence. Fear of crossing the church muted the entire village. Their silence was complicity.

Exhibit E: My Mother’s Anguish

When my mother discovered what had been done to me, her grief turned to rage. I believe she could have killed a priest if someone hadn’t intervened. She pleaded with townspeople for support. Their answer was always the same: “You can’t go against the church.” Even the RCMP discouraged her, telling her charges would only cause embarrassment. The betrayal broke her. Within months, her resolve collapsed, and she suffered a nervous breakdown.

Exhibit F: Institutional Betrayal

Decades later, in 2012, the Catholic Church contacted me for conciliation. In that process, I uncovered even more damning evidence: they had long known of his actions. In another parish less than 15 kilometers away, he had done the same. Instead of stopping him, they moved him. A predator was given new victims.

The RCMP, too, acted as his protectors. Catholic officers stationed in Cap Pelé advised my mother against seeking justice. They were right about one thing: there would be none.

Closing Argument

The Bible itself states in Matthew 18:6: “If anyone causes one of these little ones to stumble, it would be better for them to have a millstone hung around their neck and be drowned in the sea.”

So who is guilty?

- Yes, Father Camille Léger.

- But also the Catholic Church, which shielded him.

- The parishioners, who valued their faith above truth.

- The RCMP, who looked the other way.

The verdict is clear: this was not simply the crime of one man. It was the collective failure of an entire system – a conspiracy of silence that left hundreds of children in ruin.

Final Word

If truth and justice matter less to you than protecting your beliefs, your belief system is broken. In Cap Pelé, faith became an idol of fear – and truth was its first sacrifice.